My life literally changed, forever.

Sir Steve Redgrave, Henry Slade and Muhammad Ali - what do they have in common?

Yes, they are all international sporting superstars, but they are also type 1 diabetics, the condition that changed my life, forever.

From the moment they told me I might not be able to do gymnastics anymore, that was when I knew I was going to prove them wrong.

My name is Abi. I am a final year student and an ex-international acrobatic gymnast, and on the 11th September 2011, my life literally changed. Forever.

As a child I was always accident prone; I broke my elbow in the doctors, chopped the top of 2 fingers off, dislocated my knee playing chicken in the park, the list goes on. Pair that with gymnastics, the most beautiful, yet so physically demanding sport, and yes, you guessed it, an injury was bound to occur. I had been struggling with elbow pain for a while and at the shy age of 12 I was no stranger to the MRI scanner. I remember vividly my elbow locking and grinding, pain I had never experienced before, and something just wasn’t right. Needless to say, my bone had literally disintegrated off my elbow, was floating around my arm and getting jammed between the joint causing it to lock. Surgery was the only option.

I was a fit and healthy kid, always full of energy and working at 1 million miles per hour. But in the run up to my surgery my energy plummeted, like someone had just pulled the plug. I couldn’t walk up the stairs without having to rest and take a break halfway up, I lost a lot of weight very fast, I was drinking 6-7L of water a day and 2L through the night and subsequently peeing for England. My parents and I just put the behaviour down to pre-surgery nerves, when in hindsight – they are the four most import red flags for type 1 diabetes, The 4 T’s.

-

Tired

-

Thirsty

-

Toilet

-

Thinner

The day of the operation came around and it was a day surgery job – in and out in no time they thought. I lay on the hospital bed, with the anaesthetist telling me to go to a happy place and count to 10 and next thing I knew it was dark.

The surgery went well, and they removed the bone (they let me keep it!) yet my body was shutting down and it was happening fast. I have no memory of coming round from the anaesthetic, and I have brief recollections of throwing up in a plant pot outside the hospital, despite I had asked for anti-sickness mediation! However, the nurse said so long as I had had a biscuit and been to the toilet (not difficult!) I was free to come home. So, I did.

That night it become clear that something wasn’t right. I was falling in and out of consciousness, vomiting and hallucinating as my body was quickly falling into DKA – diabetic ketoacidosis. My pancreas was no longer producing insulin and subsequently my blood sugar levels were continuing to rise as my body couldn’t use the glucose as energy. My body began breaking down both protein and fat instead, resulting in an influx in ketones causing my blood to become acidic – basically poisonous. For an average person, glucose levels should be between 4.0-7.0mmol/L and Ketones 0.0-0.6mmol/L – mine were 28.9mmol/L and 6.6mmol/L for context.

After what felt like a lifetime, the morning finally came, and we got an initial, later to discover, wrong, diagnosis. The nurse predicted I had caught an infection and worst-case scenario it could be sepsis. She was pretty adamant that sepsis was out of the equation, but at this point we felt we had an answer – infection. She advised I had a meal and tried to carry on with my day, but to call back if I hadn’t improved. They actually recommended a fruit lolly and flat coke, which looking back is the worst thing to give a diabetic, but what did we know?

An hour passed, and things got worse, so we rang, we begged and back to the hospital we went.

The next stage of this story was a roller-coaster of emotions, there are days I don’t remember, things I don’t recall, but distinct moments that will stay with me forever. After stumbling back through A&E in an almost drunken state, I got assigned to a room and entered a conversation of what felt like 21 questions! I quickly got handed a pee pot and shimmied to the loo, for what I didn’t realise was going to end in me hearing the words “there is sugar in her urine, she has diabetes” - my world literally changed. Forever.

Before I even had time to blink, let alone process the news, the room became as busy as the London Underground. Doctors and nurses swarming through, people taking my blood and moving me around, all of this happening with my arm in a huge cast just 24-hrs after surgery – but this was no longer priority. They desperately needed to get an IV line in to get fluids and insulin running through my body but my veins had collapsed. They tried my arms, behind my legs, my wrists and my ankles, and after 11 attempts a line was in and everything went quiet.

So many things were going through my head, firstly, that I was going to die, secondly, why me? But the main thing was, what about gymnastics? I had come to terms with the rehab I was going to endure for my elbow, planning to be back competition fit for the end of October, but now with the addition of an incompetent pancreas and doctors telling me I couldn’t do gymnastics anymore, I knew I was going to have to prove them wrong.

I stayed in hospital for five days total, three days in ICU and two on the main ward, and in true athlete style I started setting goals. I’d heard of Sir Steve Redgrave and how successful he was, and how my grandma could carry on with her daily life with diabetes, so why couldn’t I? My sporting traits began to show, and my type A characteristics shone through; I wanted to control my diabetes well, I wanted to control it the best.

I was discharged on the 16th September 2011 and the following Monday I was back in the gym. My arm might have been in a cast and my pancreas given up, but what’s that stopping me doing leg strengthening, single arm work and choreography for the competition season ahead? Six weeks later we competed in a friendly regional champs and brought home the gold.

In the years that followed I gained National, British and International titles, competed overseas and continued to train just like everyone else. I kept my condition to myself and never liked to speak about it. I didn’t want to be known as the kid with diabetes or for people to assume I ate too many brownies as a child or was physically inactive – because Type 1 diabetes is in-fact nothing to do with diet, nothing to do with lifestyle: instead, a hereditary, autoimmune condition affecting 1 in 14 individuals, diagnosing a new patient every 2-minutes. I wanted to be just like everyone else, achieve my dreams, and prove the doctors wrong.

10 years down the line I am 4-years retired but still striving for sporting success. Keeping active for me has without a doubt helped my diabetes control. A year after diagnosis doctors were confused as to why my levels were so controlled, my HbA1C (biomarker of blood glucose control over a 3-month period) was that of a ‘normal’ individual, and 10 years on I am still in my ‘honeymoon period’. So, my pancreas is still producing some, albeit only little, amounts of insulin in the background. I put this solely down to exercise.

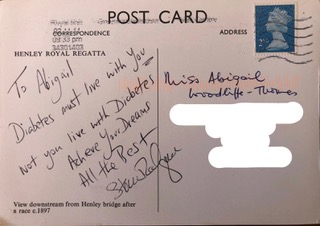

I may be a gold star diabetic student, but it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. The daily injections and blood tests embarrass me, the 3:00am kitchen cupboard raids because my levels are too low frustrate me and some days are still dark. I get the feelings of inequality, the wishes to be like everyone else, and the intense overpowering fear of people’s reactions when they find out my story. But that is why I have shared my story, to break the stigma and to help as many people as possible out there be aware of the warning signs, understand it’s not a condition provoked by poor lifestyle or bad diet, instead an autoimmune condition that I will control. In the words of Sir Steve Redgrave “Diabetes must live with you, not you live with diabetes”.

So, I urge you to be aware of the 4 T’s, educate yourself and everyone around you. Correct people if they discriminate a type 1 diabetic and assume it was self-inflicted, and finally, to never give up on your dreams.

Thank you for reading!

Some great people to follow on socials:

Comments