Just like 2020, sport can be very demanding and push us to our limits. Adversities, or any negative events, are inevitable in sport. Athletes may experience failures, mental health problems, injuries, homesickness and overtraining [1]. When dealing with these challenges, athletes are often told to just “get over it” or “move on.” We are told that in order to be successful, we must bounce back from adversity, be more resilient, and learn from our failures [2]. Yet these behaviours are not simple or easy to master.

This blog will provide you with information on resilience, why student-athletes need it, how it works and most importantly, tips on how you can become more resilient.

Why are student-athletes at risk of adversity-related stress?

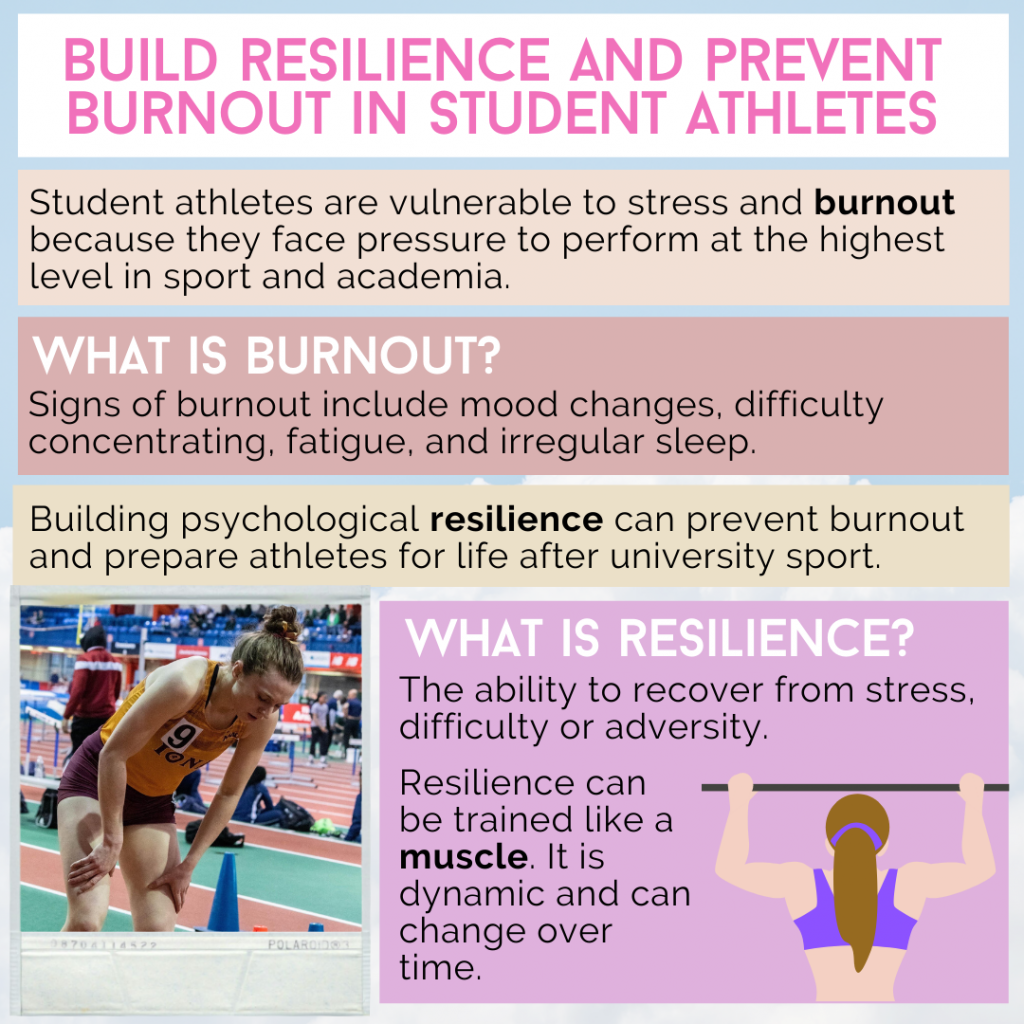

Nowadays there is an increasing pressure to perform well in every aspect of life, which can lead to burnout. Signs of burnout include mood changes, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and irregular sleep [3]. Student-athletes are vulnerable to stress because they face pressure to perform at the highest level in sport and academia [4]. Student-athlete burnout can lead to an athlete quitting their sport and possibly their education [5].

Building psychological resilience can prevent burnout and prepare athletes for life after university sport [5].

What is psychological resilience?

Resilience is often explained as the ability to recover from stress, difficulty or adversity [1], and can occur in response to a range of challenges from mild to traumatic.

Bouncing back from adversity is also a common definition of resilience [6], yet it implies that when faced with a hurdle we recover by returning to our previous state. What if we told people to move or bounce forward instead of move on or bounce back? We could learn from these challenges and use them to progress instead. Thus, bouncing forward is how I and others [8] like to conceptualise resilience.

Dr Sarkar and Dr Fletcher created the model below which explains the process of resilience [9]. When faced with stressors (adversities), athletes either positively (an opportunity for development), or negatively appraise (will hinder development), stressful events. These reactive thoughts and feelings towards the stressors, can become more positive when psychological factors are used, such as positive personality, confidence, motivation, perceived social support and focus. When these factors are enhanced, it will facilitate athletes' responses to stressors and help them cope with performance demands [9].

Previous research has described resilience as an innate, genetic trait [1], which is unhelpful for many athletes hoping to work on their resilience. However, there is evidence that resilience is dynamic and can change over time [5]. Within this concept, athletes can build their resilience like they would a muscle, through training and practice. When training the body, an athlete will want to ensure the environment around them facilitates this process, by using excellent facilities and equipment. Similarly, resilience can be developed by changing the environment around the individual, such as enhancing social support [9].

[10]

What constitutes an ideal environment for building resilience?

Researchers explored how levels of resilience in sporting environments vary based on the amount of challenge or support athletes receive [11].

Challenge

-

The expectations and demands placed on athletes, emphasising accountability and responsibility.

Support

-

Promoting a safe environment and relationship between athlete and coach through trust, guidance and feedback.

There are 4 different environments based on a combination of high or low challenge and support.

The Challenge-Support Matrix [11].

A facilitative environment is the ideal environment for building psychological resilience, thereby promoting optimal performance. Some of the features of a facilitative environment are:

-

A high level of challenge and support.

-

Promotes a strong and positive relationship between athlete and coach.

-

Constructive feedback is used and valued to learn from mistakes and failures.

-

There is healthy individual and team competition.

-

Risks are taken in a psychologically safe environment.

How do we improve resilience?

Researchers suggested that there is an interaction between a facilitative environment and personal qualities, which contribute to an individual developing a challenge mindset. This interaction means that all three factors need to be improved to see sustained resilience increase and performance success over time [11].

A Mental Fortitude Training Programme for Sustained Success [11].

Personal qualities such as personality and psychological skills, protect individuals from harm and develop resilience. Personality characteristics such as extraversion and conscientiousness are difficult to change, whereas psychological skills such as positive self-talk, imagery and relaxation, can be learnt.

A challenge mindset is one in which an individual chooses to positively evaluate stressful situations or changes negative interpretations into positive ones.

Resilience and Burnout

Chronic stress and low resilience can lead to performance slumps and athlete burnout [6]. Athlete burnout is a unique feeling of emotional and physical exhaustion coupled with a lack of success and disinterest in sport [12].

Athletes are likely to face stressors and adversities during their careers, but may not necessarily experience burnout. If athletes have high resilience, they are able to adapt and deal with stressors.

Lu and colleagues found patterns between burnout and coaches’ social support amongst athletes [7]:

HIGH resilience + HIGH coaches’ social support = LOW vulnerability to stress-induced burnout, even in environments that are highly stressful. (And Vice versa).

So, building a strong social support system is important when growing student athletes' resilience.

Resilience and Athletic Identity

Committing to one identity, such as an athletic identity, and neglecting opportunities for personal exploration (identity foreclosure), can reduce resilience and be detrimental to an athlete's wellbeing [13]. Athletic identity is the degree to which an athlete identifies with their athlete role [14].

Dr Martin and colleagues at Boise State University and Illinois State University, USA created a programme to help first-year student-athletes develop their resilience based on Fletcher and Sarkar’s resilience model [13].

The researchers adapted some of the psychological factors to focus on promoting athletes’ social support, coping resources, leadership skills, and a balanced athlete identity.

During this programme, first-year student athletes’ athletic identities naturally increased due to more time spent training and competing. Nevertheless, the programme successfully managed to help athletes’ decrease their identity exclusivity, which meant they learned to see themselves as more than an athlete [13].

With all this information in mind, I have developed a list of ways of developing resilience.

Enjoy!

Tips for Building Resilience

1. Develop a Challenge Mindset [11].

-

Reframe failure and setbacks as learning opportunities.

2. Form a balanced identity [13].

-

How you perform, is not who you are.

-

Find a balance between your sport, academics and social life.

-

Find interests away from sport because you are more than just an athlete.

3. Do not let your failures define you [15].

-

Learn from poor performances and use them to improve.

4. Motivate yourself by changing your perspective [15].

-

Think about your decision to compete and study as a choice rather than a sacrifice.

“Change your perspective from I have to train and compete to I get to train and compete” - Erin Howarth, Head Cross Country Coach at Eastern Illinois University [16]

5. Confidence is key

-

Believe in yourself and your training.

-

Identify what gives you confidence, it may be visualisation of success, looking back at your training progress or feeling the camaraderie and support of your teammates [15].

6. Actively choose to focus on your strengths.

-

Draw on previous experience when you have overcome adversity, which will help you become more resilient and confident in the present.

-

Write your strengths down and remind yourself of them every day [17].

7. Maintain focus [9].

-

Focus on the process and not the outcome.

-

Focus on you, nobody else.

8. Focus on what you can control.

"I focus on controlling the controllable, which is me."

- Dina Asher-Smith [18].

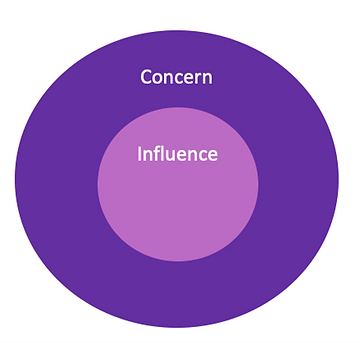

The Circle of Influence and Control is a helpful tool from Stephen Covey’s book, the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People [19].

The circle of concern refers to all the parts of your life you care about but have little control over. In contrast, the circle of influence refers to the parts you have direct influence and control over, such as how you respond and interpret adversity.

With the overwhelming presence of social media in today's society, we constantly compare ourselves to others. We focus too much on our circle of concern and the people and things that are out of our control. Covey suggests that highly effective people focus on increasing their circle of influence. The circle of influence works like a muscle, because when you focus your time and energy on what you can influence, this will expand your knowledge and experience, just like a muscle grows and strengthens [19].

9. Strengthen your social support network [9].

-

Establish and use your network of coaches, teammates, family and friends for encouragement, support, advice and feedback.

Author's Note

I hope this blog has given you an insight into the importance of resilience in sport and provided you with helpful tips for the future. Please share your thoughts in the comment section below or contact me directly. Finally, remember, keep showing up and do something every day until you reach your goal.... then set new ones!

References

[1] Fletcher D, Sarkar M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1):12-23.

[2] Syed, M. (2015). Black box thinking: The surprising truth about success. Hachette UK.

[3] Sudano, L. E., Collins, G., & Miles, C. M. (2017). Reducing barriers to mental health care for student-athletes: An integrated care model. Families, Systems & Health. The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 35(1), 77-84. https://doi:10.1037/fsh0000242

[4] Etzel, E. F., Watson, J. C., Visek, A. J., Maniar, S. D. (2006). Understanding and promoting college student-athlete health: Essential issues for student affairs professionals. NASPA Journal, 43, 518-546.

[5] Sorkkila, M., Tolvanen, A., Aunola, K., & Ryba, T. V. (2019). The role of resilience in student-athletes' sport and school burnout and dropout: A longitudinal person-oriented study. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 29(7), 1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13422

[6] Galli, N., & Vealey, R. S. (2008). "Bouncing back" from adversity: Athletes' experiences of resilience. The Sport Psychologist, 22(3), 316–335. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.22.3.316

[7] Lu, F. J. H., Lee, W. P., Chang, Y.-K., Chou, C.-C., Hsu, Y.-W., Lin, J.-H., & Gill, D. L. (2016). Interaction of athletes' resilience and coaches' social support on the stress-burnout relationship: A conjunctive moderation perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.005

[8] Haas, M. (2016). Bouncing Forward: The Art and Science of Cultivating Resilience. Simon and Schuster.

[9] Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(5), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007

[10] den Heijer, A. (2018). Nothing You Don't Already Know: Remarkable Reminders about Meaning, Purpose, and Self-realization.

[11] Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7, 135-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

[12] Dubuc-Charbonneau, N., & Durand-Bush, N. (2015). Moving to action: the effects of a self-regulation intervention on the stress, burnout, well-being, and self-regulation capacity levels of university student-athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 9(2), 173-192

[13] Eric Martin, Ph.D. Scott Pierce, Kelly Rossetto, Liam O’Neil. (2018). Resilience for the rocky road: Supporting first year student-athletes in their transition to college. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1822968

[14] Kerr, G., & Dacyshyn, A. (2000). The retirement experiences of elite, female gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200008404218

[15] Sarkar, M. (2019, June 3). Nine ways to develop resilience as a student athlete. Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme. https://www.tass.gov.uk/2019/06/03/nine-ways-to-develop-resilience/

[16] Howarth, E. (2020). “Change your perspective from I have to train and compete to I get to train and compete.”

[17] Chandler, G. E., Kalmakis, K. A., Chiodo, L., & Helling, J. (2020). The Efficacy of a Resilience Intervention Among Diverse, At-Risk, College Athletes: A Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390319886923

[18] McGuire, J. (2020, March 12). The golden-girl of athletics and the importance of mindset. Runner’s World. https://www.runnersworld.com/uk/training/motivation/a31423300/dina-asher-smith-tokyo-2020/

[19] Covey, S. R., (1989). Seven Habits of Highly Effective. Free Press.

How Can Student-Athletes Build Resilience and Prevent Burnout?

Written by Helena Keenan

If you would like to collaborate, get in touch here, on socials, or at info@theathleteplace.com.

theathleteplace are proud to work with and promote athletes & content creators to produce what is needed to benefit those in need.

Comments